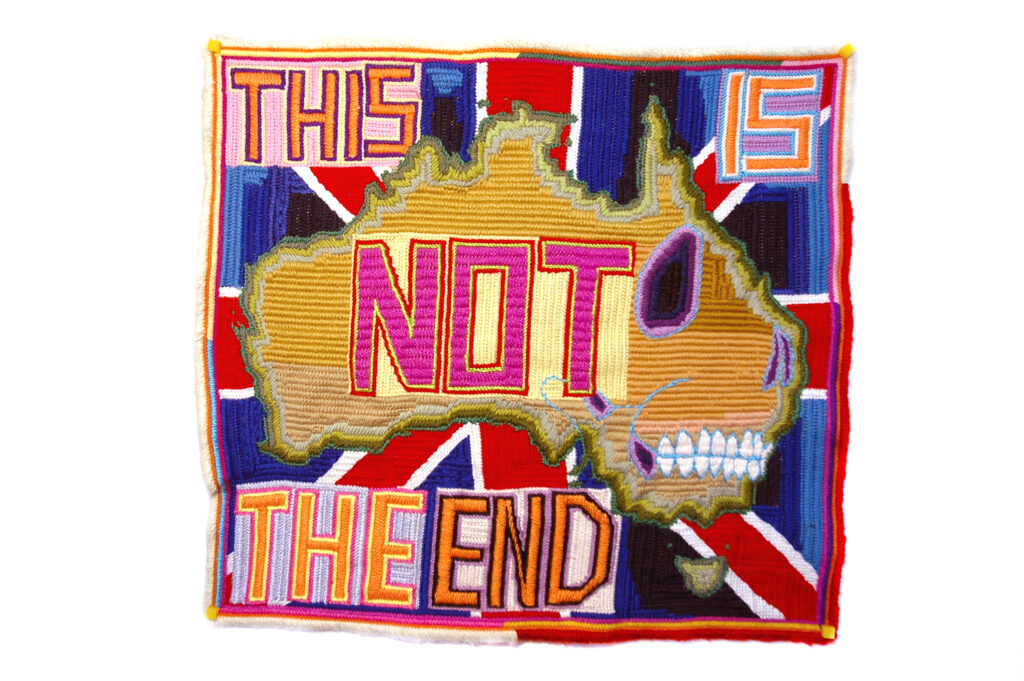

Australian artist Paul Yore implores our attention with his exhibition “Patriot” at Michael Reid gallery, which deals with the slipperiness of language, the limitations imposed by borders and boundaries, the weight of competing historical narratives and the prevailing cultural climate that feels at once foreboding and yet full of potentiality.

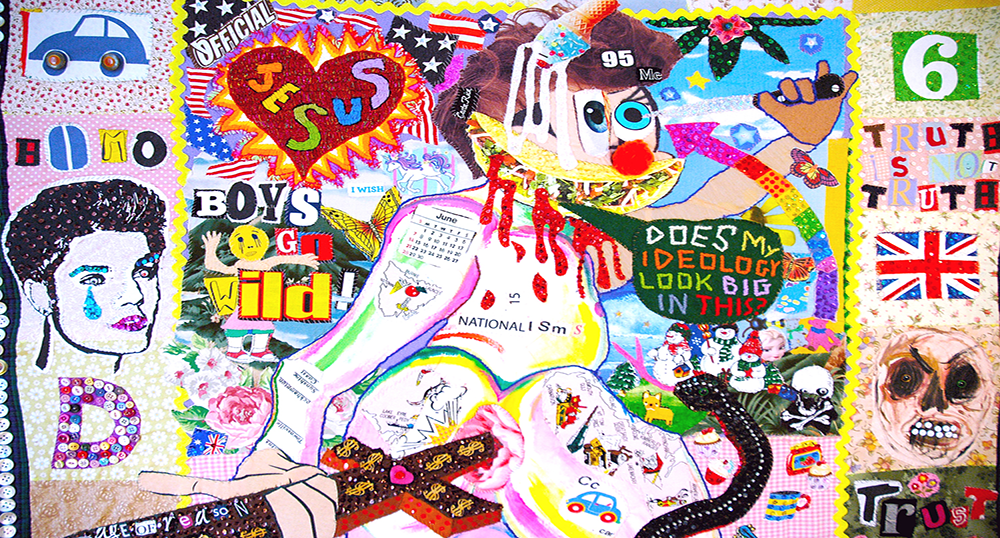

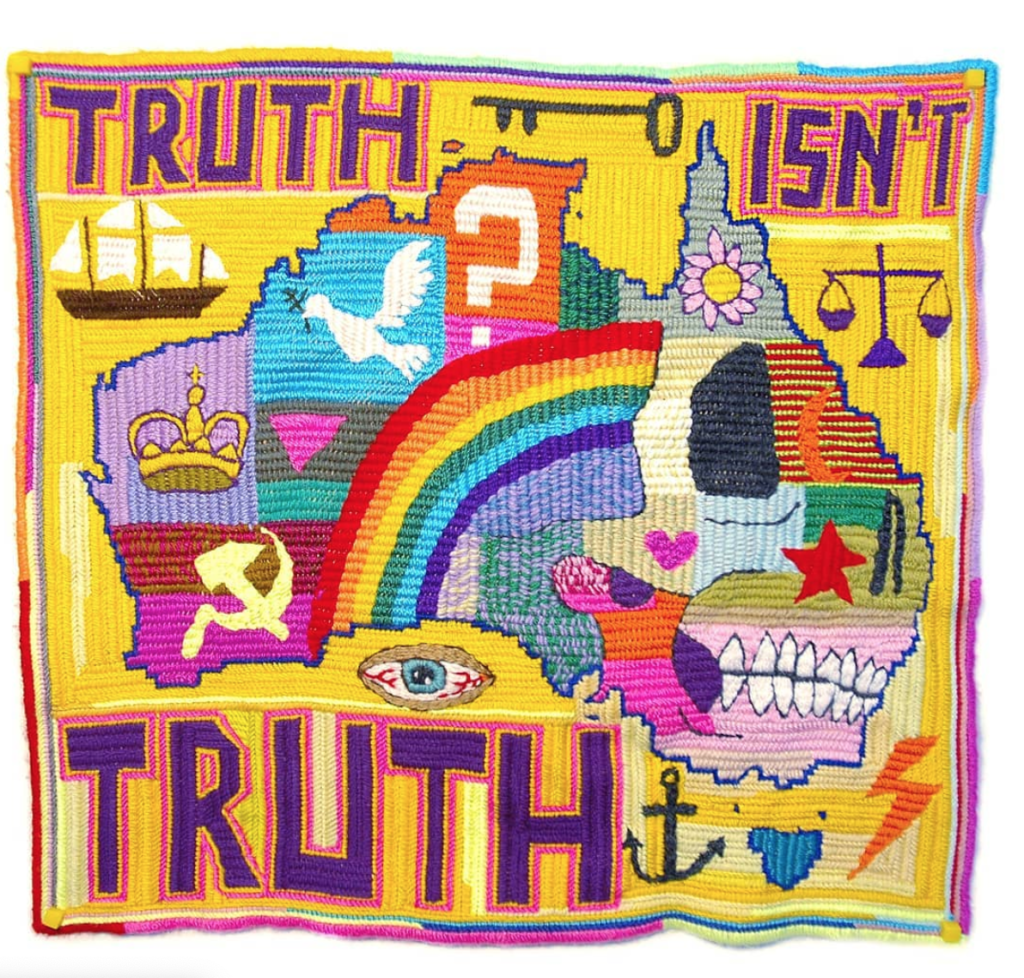

The artist’s works present intensely layered, textile forms, often employing needlepoint, quilting, and appliqué techniques comprised of a medley of text and imagery that aim to mirror and critique society and lived experience. In Australia the artist is seen sometimes as a troublemaker because he lays all aspects of Australian identity bare for examination. No stitch is neutral. Anecdotes of kitsch Australiana collide with visual cues identifying topics such as colonial undercurrents, religious conservatism, censorship and strategic international alliances signifying decline and collapse.

“As a queer person, I see my work as inherently political. I am interested in positing counter-narratives that challenge the problematic assumptions that underpin hegemonic cultural norms.”

We chat to Paul and find out what it was like growing up in strict Catholic community as a queer teen, his road into art, what’s been keeping him sane during lockdown and the most overrated part of being an artist.

Hi Paul, what drew you to quilting, appliqué, needlepoint and embroidery as techniques for your artistic expression and production?

About ten years ago, I experienced a mental health episode that left me held in a psychiatric facility undergoing treatment involving strong medication. In the months following this incident, I had very little energy or motivation to do anything at all. It was in this context that I began embroidering with some wool and canvas, teaching myself and improvising the stitching as I went. I was not thinking about art at the time, I just wanted an activity to take my mind off the way I was feeling. I found embroidery incredibly cathartic, and, as I continued working, began to see the enormous potential of the textile medium in expressing my ideas. I branched out into other traditional textile methodologies, and now work predominately in applique and needlepoint.

Take us through your artistic process from the formation of the idea to the construction and completion of the piece. How long does the construction typically take?

At the outset, I usually make rough preparatory sketches for large works, and then I pick out fabrics and other materials. Most of the process is quite improvised and intuitive, I cut up small pieces of fabric, and they are pinned into the work. This process can take many months. Once I am happy with the whole design, I begin hand sewing everything down. This usually takes a few weeks. Then finally embellishments are added – sometimes lace or decorative trim, and many buttons, beads and sequins are hand sewn into the work, this also takes several weeks. So all and all it is a very long and slow process!

You are from Melbourne but you currently live and work in Gippsland. What inspired your move?

My partner and I have wanted to move from the city to the countryside for some time, to get away from distractions and focus on making art. We really love the pace of life and the fresh air, growing our own food and being around trees, birds and all the rest of it. It is very peaceful, apart from the occasional Eastern Brown Snake! My mother grew up in Gippsland, so it is not entirely unfamiliar for me.

Your current exhibition PATRIOT deals broadly with the slipperiness of language, the limitations imposed by borders and boundaries, the weight of competing historical narratives and the prevailing cultural climate that feels at once foreboding and yet full of potentiality. How has living in Victoria which has been widely criticized as a nanny state influenced your work? & how important is it to you to have a strong social and political voice as an artist and creator?

As a queer person, I see my work as inherently political. I am interested in positing counter-narratives that challenge the problematic assumptions that underpin hegemonic cultural norms. My work is in part informed by anarchist philosophies that view all forms of state or government as innately antithetical to the pursuit of freedom, so the idea of the nanny state is an interesting one. In Australia, I see this as a broader question as Australia is not a Republic, and has no Bill of Rights, let alone a Treaty with First Nations peoples.

You identify as queer and have said that you grew up in a strict Catholic household, can you tell us a bit about your upbringing and your road into art

Well, I actually feel I had quite a regular upbringing, however I always felt an inherent conflict between the religious beliefs of my family, and my own queer identity. I found the Catholic education system particularly challenging; when you are queer, trans or questioning your sexuality or gender identity, it is vitally important that you have access to information that affirms your experiences. Without this normalising affect, it is very easy for LGBTIQA+ youth to feel isolated and this can in turn have serious consequences, as sadly so many of the statistics around self-harm, suicide, homelessness and substance abuse bear out.

What have you been doing to stay sane during lockdown?

Making art of course! Beyond this, I have been gardening a lot during lockdown. Now that we live rurally, we are aiming to grow a lot of our own fruit and vegetables, which is a lot of hard work but very rewarding. Simply spending time outside and observing the seasons and patterns of the natural cycles is very calming, even if it is just picking the caterpillars off the cabbages…

Tell us one recipe that you’ve mastered

The only recipes I seem to master are recipes for disaster!

What the most overrated part of being an artist in your opinion

I think many view the lifestyle of the artist as quite fun and exciting, but in reality it is a lot of hard work, almost always involving many years of juggling several jobs to support your practice, and often working for free or at a loss.

What’s the weirdest thing that you love that most people hate

I have to admit I quite love snakes and spiders, and any creepy-crawlies really. Dangerous and potentially deadly creatures are a big part of Australian ecology, forming a part of the landscape, I really love that.

“Patriot” is running at Michael Reid gallery in Berlin until the 19th of December.